Since TIFF’s first direct investment alongside an independent sponsor in 2014, we have completed more than 60 deals with over 25 different sponsors, making TIFF one of the most active institutional capital providers in the market. Over the past decade, the market has evolved significantly, and our approach to working with independent sponsors has evolved alongside it.

When we began investing in this space, we believed independent sponsors could serve as both a great source of attractive returns on individual deals and as potential long-term partners for fund commitments. We viewed this work as an extension of TIFF’s longstanding history in the lower middle market and our commitment to partnering with emerging managers. Expanding our direct investments into the independent sponsor arena offered a firsthand view of compelling lower middle market opportunities (which we generally define as companies with less than $100M in revenue or $25M in EBITDA), while allowing us to build relationships with high-potential managers well before they raised their first fund.

Our aim was to create a virtuous cycle around our sponsor diligence and deal diligence, leveraging our deep experience in fund underwriting to identify and assess exceptional independent sponsors while also relying on our direct investment experience to underwrite transactions alongside them. By examining both the sponsor and deal, we expected to improve our insights into each opportunity.

We believed the thesis was sound, but we did not know how it would play out in practice. More than a decade later, we can safely say the strategy has exceeded our expectations, resulting in meaningful partnerships with independent sponsors and access to compelling investment opportunities. Importantly, we have had a front row seat for the development of the independent sponsor market itself. With more than ten years of experience, we reflect on what has changed, what has remained consistent, and what we have learned.

Observation 1: The independent sponsor market has exploded in scale

The number of new PE firms continues to expand, many of which begin as independent sponsors. While no consistent data set exists on the number of independent sponsors in the market or the number of traditional PE firms that began as independent sponsors, the expansion is evident in deal activity, market events, TIFF’s own CRM, and even our inboxes. A decade ago, encountering an independent sponsor was relatively rare; today, the universe has grown, encompassing a wide range of independent sponsor types and profiles. The ecosystem of lawyers, lenders, intermediaries, and investors catering to these sponsors has expanded as well, highlighting the market’s maturation.

Observation 2: The independent sponsor deal model is gaining acceptance

While the independent sponsor model has existed in various forms for decades, its success over the past several years, both in terms of deal-by-deal returns and in serving as a pathway to raising a committed fund, has attracted more seasoned investors who have left established PE firms to launch their own independent platforms. This shift has raised the overall quality of professionals in a market that was previously populated largely by younger investors without an attributable track record, ex-bankers or consultants seeking to transition into investing, or operators pursuing deals in their niche areas of focus.

Observation 3: Capital structures and economic terms continue to evolve

Similar to the broader private equity universe, terms in the independent sponsor market continue to balance manager and investor interests. In our view, terms for independent sponsor deals are more clearly structured to align interests between investors and sponsors. Monitoring fees based on EBITDA and tiered carry structures, now relatively standard across deals we see in the market, create stronger incentives for equity value creation compared to most private equity investments. Rather than charging a flat fee and significant carried interest for minimum performance, independent sponsors must grow EBITDA and return high multiples of money to generate significant wealth. On occasion, we see an independent sponsor try to negotiate for a “premium carry” tier of 25%, but these negotiations are typically not successful and would only apply in truly outsized returns scenarios.

In an attempt to bridge the gap between an one-off deals and fully-fledged funds, we have seen pledge fund-like structures grow in popularity. These structures involve an investor and manager agreeing to certain terms and investment amounts in advance of any specific transaction. They typically include a small management fee, with the investor retaining the option to decline any individual deal. These structures can blur the line between deal-by-deal investing and traditional fund commitments in troublesome ways, providing neither the capital certainty of a fund nor the deal-specific alignment of typical independent sponsor deal.

Observation 4: The lower middle market remains an attractive and under-capitalized space

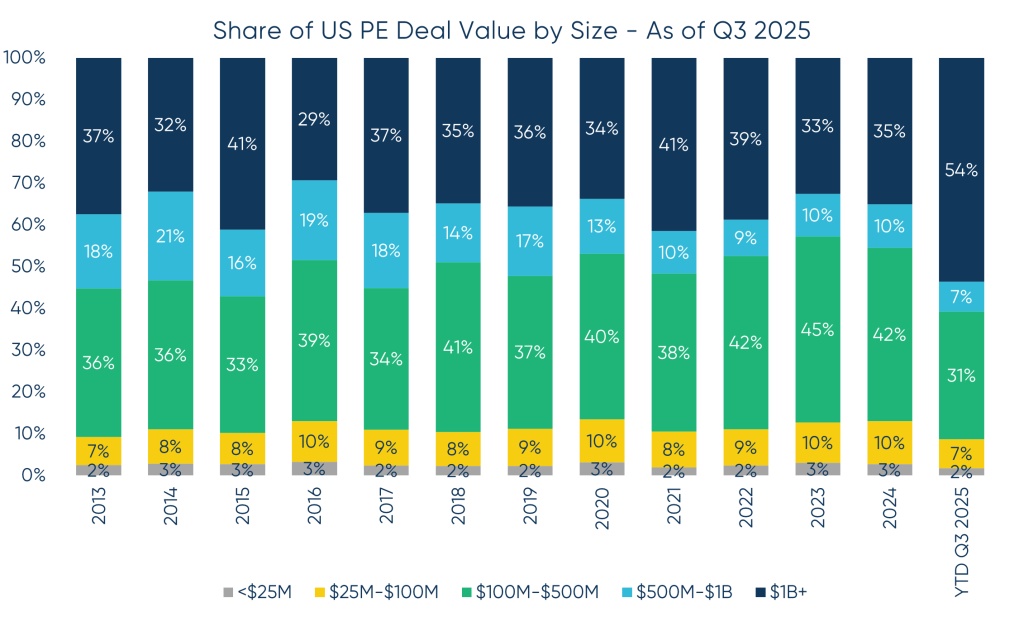

Given typical deal sizes and the ability to add value through improved strategy and operations, most independent sponsors play in the lower middle market. Yet, this segment represents only a fraction of overall U.S. deal volume. According to PitchBook data on the U.S. PE market, deals valued less than $100M have consistently accounted for between 11% and 13% of total transaction volume from 2015 through 2024. Deals valued at less than $25M, which is consistent with the range targeted by independent sponsors, have consistently represented between 2% and 3% of total deal volume since 2015.1 Despite growth in the independent sponsor market, this segment still represents a relatively small part of the broader PE market. This relative scarcity reinforces the opportunity: fewer competitors, lower entry valuations, and greater inefficiency create fertile ground for differentiated sponsors.

Observation 5: Attractive valuations continue to create compelling entry points

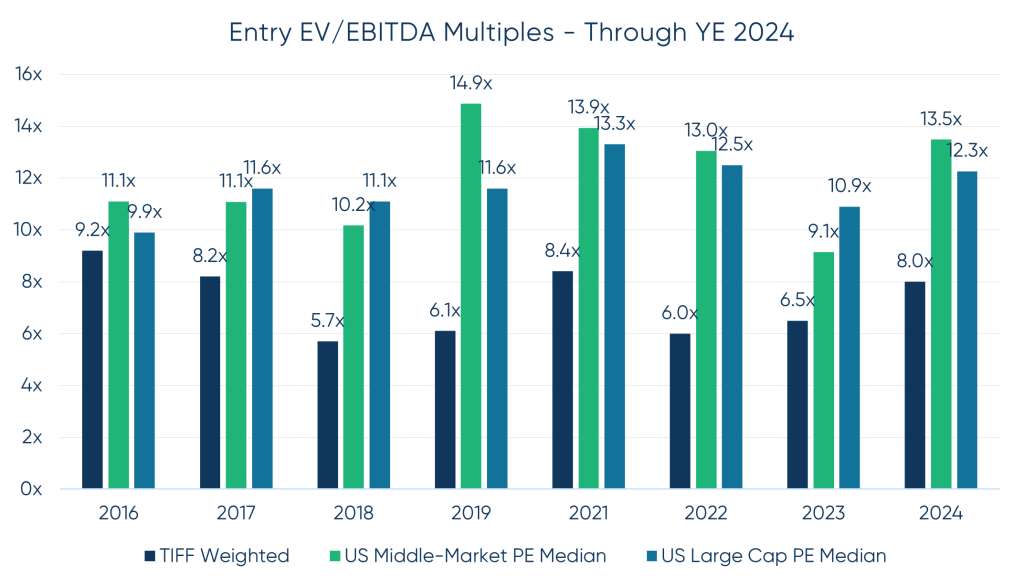

Despite the rapid growth in the independent sponsor market and rising interest in the lower middle market by private equity, deal valuations are still well below market medians. According to the McGuireWoods Independent Sponsor Survey in 2024, 54% of independent sponsor deals were completed at EV/EBITDA valuations less than 6.0x.2 For TIFF’s own direct deals, we have averaged between 5.7x and 8.4x EV/EBITDA acquisition multiples since 2018.3 Comparatively, median private equity multiples in both the middle-market and large-cap segments are dramatically higher. Middle-market multiples have stayed between 10.2x and 14.9x while large-cap multiples have stayed between 11.1x and 13.3x.4 One would expect smaller companies to trade at lower valuations, but these independent sponsor deals are still priced well below median market multiples in larger market segments.

Observation 6: Institutional investors are still largely absent

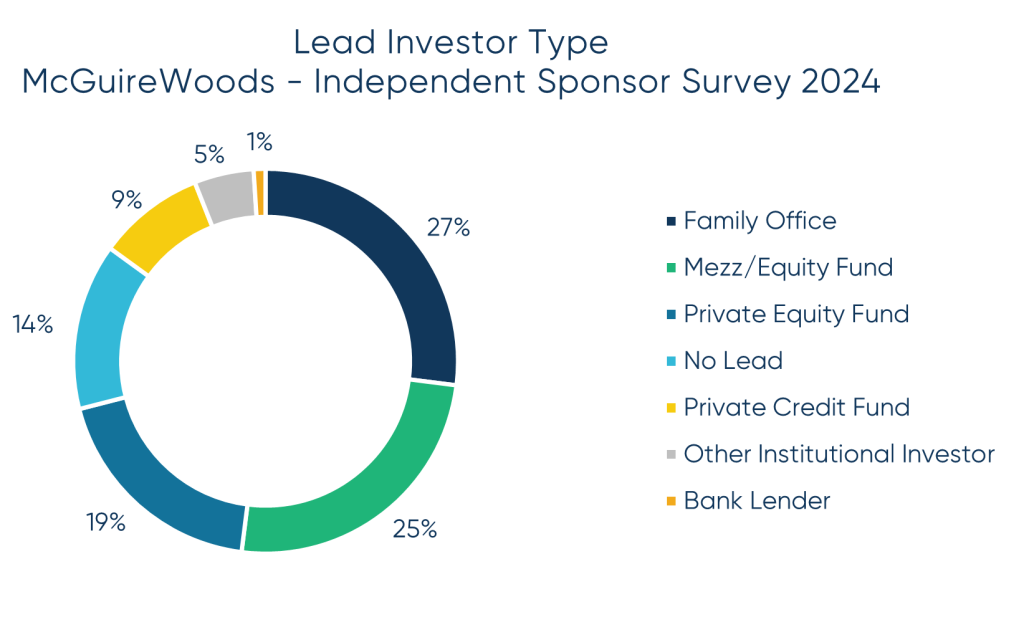

While the market has grown and more institutional investors recognize the return potential in the lower middle market, many still remain on the sidelines when it comes to investing with independent sponsors. There is limited historical data on market participation by investor type, but across deals from 2021 through 2024, only 5% of lead investors were institutional investors. Most deals were led by family offices, mezzanine or equity funds, or other private equity funds.5 In Citrin Cooperman’s 2024 Independent Sponsor Report, only 11% of capital for independent sponsor deals came from institutional investors.6 Despite the broader expansion into private equity by institutions, they have yet to enter the independent sponsor market in a meaningful way.

Why have institutions mostly avoided this segment so far? Institutions are not monolithic, but several likely reasons are at play. The average investment size for independent sponsor deals is generally quite small for most large institutions (close to 50% of independent sponsor deals have a total enterprise value of less than $25M).7 Investment teams at these institutions are also rarely staffed to evaluate direct opportunities quickly and effectively. Additionally, institutional risk appetite tends to be relatively low, with a preference for more “traditional” investment structures even at the expense of higher returning opportunities. As a result, the independent sponsor market has remained the domain of more adaptable investors who have team structures in place that are better suited to take advantage of the market’s distinct dynamics.

Observation 7: Access to follow-on capital can make or break deals

Regardless of the plan at the outset of an investment, something will likely deviate from plan. Growth may not materialize as expected, macro conditions could worsen, interest rates may fluctuate, key team members could leave, etc. It is common for investments to require more capital than originally anticipated. This is particularly true for minority growth equity investments in businesses that are cash-flow neutral to slightly negative. Even if the sponsor puts cash on the balance sheet at close and expects the business to be cash flow positive going forward, one small operational hiccup can quickly lead the company to require additional capital.

For investments made from a fund, a larger pool of capital is available at the sponsor’s discretion to support the initial investment and to provide growth or rescue capital as needed. For independent sponsors, having experienced investors around the table is critical for navigating any potential headwinds or additional cash needs. Consistent and committed investors who understand the dynamics of lower middle market company performance, and who can over-equitize businesses at the outset or provide follow-on capital when appropriate, can dramatically improve the odds of successful investment outcomes.

Observation 8: Portfolio construction is essential to long-term success

Investing in independent sponsor deals requires consistency and discipline to build a strong portfolio. The risk profile of companies in the lower middle market, combined with the risks of investing with less proven or less experienced managers, requires a portfolio approach to achieve strong long-term returns. The range of return outcomes for any single deal can be wide, so diversification across managers, companies, sectors, and deal profiles can help mitigate some of the risks inherent to this market while maximizing the opportunity to achieve superior returns over a multi-year investment horizon. A portfolio approach also creates more opportunities for learning from deal to deal and from sponsor to sponsor. Approaching the independent sponsor market in a fleeting or haphazard manner is a recipe for disappointment.

Observation 9: Sponsor diligence is just as critical as deal diligence

The independent sponsor market blends manager selection with deal selection. When done well, investing in the market can create a virtuous cycle in which strong manager diligence builds confidence in the sponsor’s thesis, diligence, and value-add plan, while strong company diligence informs a perspective on the manager’s areas of strength and weakness. Success begins with the ability to source, evaluate, and partner with exceptional managers in the independent sponsor market. As the market has expanded, more experienced and high-potential managers are launching as independent sponsors, but more low-quality or undifferentiated managers enter the market as well. In our view, having a clear view of what defines an exceptional sponsor is essential for long-term market success.

Observation 10: Consistent success is predicated on long-term partnerships between sponsors and investors

As in any market showing promise, the independent sponsor landscape has attracted participants looking for quick wins with little focus on long-term success. Our experience, however, has demonstrated that patience in selecting the right sponsor and deal opportunity, diligence to evaluate all aspects of a transaction, and alignment of interest between investors, sponsors, and company management are all essential elements in generating strong returns over time. This approach builds trust between investors and sponsors, creating durable partnerships that span multiple deals in which all participants make vital contributions to investment success. While one-off transactional arrangements in this market may appeal to inexperienced investors, we remain focused on building and maintaining our long-term partnerships with exceptional sponsors.

Conclusion

After a decade of active participation, we see the independent sponsor market as more attractive today than when we began. The market is deeper and more professionalized, valuations remain well below mainstream PE levels, and institutional competition is still limited. This combination — depth without crowding — creates fertile ground for identifying attractive opportunities to generate outsized returns. Our focus remains unchanged: partnering with exceptional managers to back differentiated lower middle-market companies.

As TIFF enters its second decade of independent sponsor investing, our conviction has never been higher. We believe this direct deal strategy has delivered outstanding results while building meaningful partnerships with our sponsors. We will continue to build on these relationships and the insights gleaned over the past ten years to refine our process, focus our approach, and maintain the same level of diligence and rigor that has been central to this strategy since 2014.

The materials are being provided for informational purposes only and constitute neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of an offer to buy securities. These materials also do not constitute an offer or advertisement of TIFF’s investment advisory services or investment, legal or tax advice. Opinions expressed herein are those of TIFF and are not a recommendation to buy or sell any securities.

These materials may contain forward-looking statements relating to future events. In some cases, you can identify forward-looking statements by terminology such as “may,” “will,” “should,” “expect,” “plan,” “intend,” “anticipate,” “believe,” “estimate,” “predict,” “potential,” or “continue,” the negative of such terms or other comparable terminology. Although TIFF believes the expectations reflected in the forward-looking statements are reasonable, future results cannot be guaranteed.

Footnotes

PitchBook, Q3 2025 US PE Breakdown, published October 10, 2025.

McGuireWoods, 2024 Deal Survey of Independent Sponsor-Led Transactions, accessed October 2025.

TIFF Data on deal multiples by year for direct deals acquired on an EV/EBITDA basis.

Data from PitchBook as of Q3, 2025; Large cap is defined as deals valued at over $5B.

McGuireWoods, 2024 Deal Survey of Independent Sponsor-Led Transactions, accessed October 2025.

Citrin Cooperman, 2024 Independent Sponsor Report, accessed October 2025.

McGuireWoods, 2024 Deal Survey of Independent Sponsor-Led Transactions, accessed October 2025.